Vision

Scripture tells of a heavenly city where chosen people from every nation and tongue gather together to worship God. When Jesus returns we will finally see this city perfected, the way it was meant to be. But even now we see vivid glimpses of it in our local congregations. In cities around the world, believers are joining hands across cultural barriers and lifting their voices together in praise of their Savior.

Many musicians leading this worship have been trained at New City Fellowship. This site hopes to further extend this movement, offering music, video, instruction, and reflection for those who want to take part in the vision of cross cultural worship.

Like the New City congregations that support us, we are passionate about the Biblical view of racial reconciliation through Christ. Yet we recognize the difficulty of cross-cultural ministry. Our unique histories and dreams, beliefs and biases, images and idioms, often seem at odds. But through the Lord our different lives interlock. In Christ we find the places where the pieces bind.

A pastor's gracious words or a deacon's loving deeds, in their own way, can help to heal racial fallout. Likewise, a musician's songs of praise can unite peoples who were once divided. The challenge of the cross-cultural worship leader is to search out the cultural angles that connect, the grooves that go together.

History

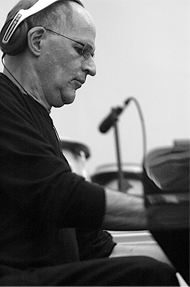

James Ward, Former Music Director at New City Fellowship in Chattanooga, has found that uniting diverse cultures in praise requires working the middle ground between musical heritages. While studying music at Covenant College in the late sixties, Jim began leading Sunday worship at the downtown Chattanooga ministry that would eventually become New City Fellowship. Backed by a team of like-minded musicians, he searched for a musical language to express the new ministry's cross-cultural vision. Though he had grown up playing European Protestant hymns in white Presbyterian churches, he began to visit local black churches and black choir concerts. He wanted to find the places where the two traditions met. “We were trying to create a language of praise that didn't come from the extremes of white culture or black culture,” says Jim. “We wanted it to come from a common ground: hymns that both blacks and whites knew. By visiting black churches, we saw the raw energy and identity of the worshippers with specific songs and forms.”

When he turned to the Trinity Hymnal, and to contemporary Presbyterian worship songs, Jim found few hymns that black Protestant Christians had embraced. At the same time, he found few modern Gospel songs that were being sung by white Protestant Christians. So he mined deeper into the Church's musical history in search of material. In the rich store of nineteenth century British and American Gospel songs he found hymns that were dear to both white and black Christians.

As he was building his repertoire of cross-cultural praise songs, Jim also developed his ability to synthesize the distinctive worship styles of the two different traditions. If you were to step inside the sanctuary of New City Fellowship this Sunday during praise time, you might hear the band playing “In Christ Alone,” a Townend-Getty hymn in the tradition of great nineteenth century songwriters like Isaac Watts and Charles Wesley. Though it is typically sung in a Celtic style, the band may sing the hymn in the three part harmony common in black Gospel. They might also add grand breaks and accents that reference the dramatic gestures of Gospel music. “Celtic music wouldn't do it like that, and white churches wouldn't do it like that,” he says, “but at a church where we have blended cultures, an impassioned delivery of a specifically white song is very helpful for bringing the congregation together.”

As in any cross-cultural ministry, unity doesn't come naturally. Even after carefully choosing songs and molding their styles, we must persuade the congregation that unfamiliar music can be a part of their own heart language. When introducing a black Gospel song to a congregation, James will give instruction on how to sing along to its melody and clap to its rhythm. In the same way, traditional European hymns like “Beneath the Cross of Jesus” are unfamiliar to some African American worshippers, and must be introduced inclusively. He will also encourage reluctant white worshippers to step outside their own cultural comfort zones and engage the song in new ways. Both black and white members are given a similar nudge when he introduces a Spanish song into Sunday morning worship. In this case, he or one of his singers will usually introduce the song with a brief Spanish-to-English translation. When leading a diverse crowd in worship, thoughtful presentation is as important as the songs themselves.

These are just some of the tools that Jim has developed over 30 years of leading worship at New City Fellowship. These are the tools that many have carried away from their time in training here. This website is another means of spreading this wealth, encouraging musicians and worship leaders across the country with the experience and legacy of New City music.